Towards a model of digitalization

This post is in progress and may change over time. Do give feedback, or come back later to see how it develops.

Where is the Life we have lost in living? Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

T.S. Eliot

I was asked to contribute a book chapter on predictive maintenance (forthcoming) and used this opportunity to think about how my subject area, Digital Transformation, could support it.

Initially, I thought there was not much overlap, but it soon turned out that the disciplines are dealing with quite similar phenomena. In predictive maintenance, the effort is on analysing running systems (e.g. machines or railways) in order to detect faults early on. In Digital Transformation, we also try to analyse data from live systems (which could be anything from transactions in an online shop to bookings for train or bus tickets to…?) and draw conclusions from it.

Next, I thought about what actually happens in these processes. What are the relevant facts of the world, how are they digitized (Verhoef et al. 2021) and how are decisions made based upon them?

I thought I’d start with a relatively simple, everyday process: the use of a smart watch to track an individual’s physical activity. Here, for example, the interesting facts are the number of steps that person is taking during a day. Having these available could ideally motivate them to walk more, if necessary.

How to describe this in more precise terms? What is the data here, what is the information?

Background: IS defining data (or not)

Unfortunately, the Information Systems (IS) literature is notoriously bad at using the terms ‚data‘ and ‚information‘ with sufficient precision (McKinney& Yoos 2010). If you subscribe to the token view (the most common one according to McKinney & Yoos), information is synonymous with data.

Looking at the Management literature, there are more straightforward definitions. According to Laudon (2014, p. 609), ‚data‘ are defined as “streams of raw facts” and ‚information‘ as “data that have been shaped into a form that is meaningful and useful to human beings” (p. 612). Starting from facts is definitely useful, as we ultimately want to find out about events in the physical world. In a German book on information management, Krcmar (2015, p. 11) discusses the a hierarchical view of codes, data, information and knowledge. Syntax turns codes into data; context adds meaning to data, thus creating information. This is a useful view as it clearly distinguishes between the four different concepts.

Digitization is described by Verhoef et al (2021, p. 891) as „the encoding of analog information into a digital format (i.e., into zeros and ones) such that computers can store[,] process, and transmit such information“, which is a useful definition, except we don’t know yet what information is, so will avoid the term and stick with „signs“.

Certainly, at this point, we can claim that there are enough differences between data and information to warrant using different terms.

Model

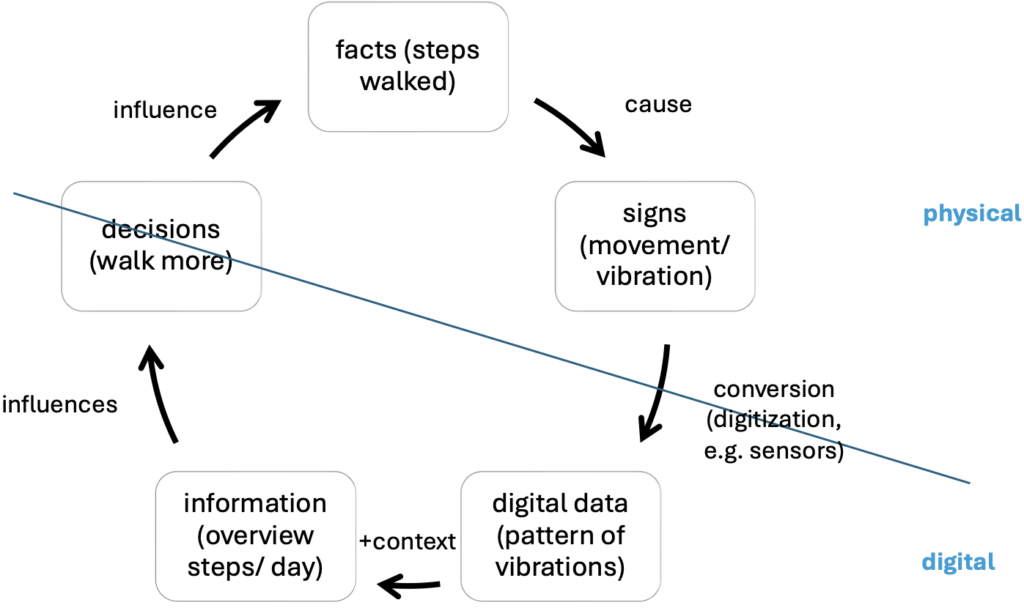

Based on the above, and some earlier thoughts of mine, I wanted to start from the facts of the world and see how they become digitized. Here’s the model I came up with;

Looking at the example of the smart watch,

- the facts (steps taken) cause signs that can be measured (in this case, specific patterns of movement in the watch)

- the signs are then digitized using the motion sensor in the watch, so they are turned into digital data corresponding to a specific pattern of vibrations indicating a step has been taken.

- This raw digital data is not useful in itself, but can be presented in a way that is, i.e. turned into information. This could be done by adding context to the data or by formatting it in a way that is meaningful to its users.

- In the end, the watch will give a piece of information (e.g. number of steps taken on this particular day, ideally compared to a target value that was defined before).

- This is presented in a way that enables (informs?) decision-making, in this case, potentially walking some more.

- Obviously, and crucially, this also affects the original facts (number of steps).

This can relatively easily be transferred to the realm of predictive maintenance: Here,

- the starting point of the process is facts about the world, e.g. the the condition of a machine.

- These cause signs in the physical world, e.g. movement or vibration.

- These are then converted into digital data, e.g. by sensors.

- This digital data can be enriched with an appropriate context and used as information in order to support decisions.

- The decisions that are made in this way in turn affect the original facts (e.g. the maintenance interval of the machine is adjusted).

A closer look

Let’s take a closer look at where the data comes from. Especially in predictive maintenance, it is clear that it is not the facts of the world being digitised, but certain signs in the physical world indicating them. Specifically, it’s not the mechanical condition of the railway track itself, but the measurable signs indicating this condition, e.g. slight variations in the movement or vibration patterns of the train. These are turned into digital data and, by contrasting this with previous data, a context is established that can yield information about the track’s condition (specifically whether it is damaged). This can inform decisions (e.g. adapting the maintenance intervals for the track), which again influence the initial facts (the track’s condition).

What to make of it?

I hope this model can be useful also for researchers and practitioners working on other aspects of digitalization/ digital transformation.

- In projects on digital transformation, consider what are relevant facts that should potentially be analyzed. How can these facts be digitized?

- If these facts are not obvious/measurable in themselves, are there any signs that can be used instead?

- Next, once you have digital data available, consider what information is needed in order to support decisions. How are you going to present the data, and what context, if any, do you need to add?

- …

References

- Krcmar, Helmut. Informationsmanagement. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2015.

- Laudon, Kenneth C, 1944. Management Information Systems: Managing the Digital Firm. Harlow, England: Pearson, 2022.

- McKinney, Earl H., and Charles J. Yoos. “Information about Information: A Taxonomy of Views.” MIS Quarterly 34, no. 2 (June 1, 2010): 329–44.

- Verhoef, Peter C., Thijs Broekhuizen, Yakov Bart, Abhi Bhattacharya, John Qi Dong, Nicolai Fabian, and Michael Haenlein. “Digital Transformation: A Multidisciplinary Reflection and Research Agenda.” Journal of Business Research 122 (January 1, 2021): 889–901.